Mark Brezinski featured in D Magazine

November 13, 2020 3:17 PM PST

After a spectacular rise and fall, the father of Dallas’ fast-casual food scene is ready for his next big hit.

The Redemption of Mark Brezenski

Even in a line of customers wrapped around a Carrollton strip mall eager to get inside the newest outposts of one of the world’s largest udon concepts, it was easy to pick Mark Brezinski out from the crowd.

At 6’4″, he towers over most. But it wasn’t his considerable stature that caught my eye. It was the blithe spirit conveyed by a slightly crooked smile, revealed by a sagging face mask. Celebrated as the father of Dallas’ fast-casual food scene, Brezinski’s career has spanned four decades and touches some of the area’s most popular food chains. But you’d be hard-pressed to learn much about the man online, despite the fact that he has participated in more than 120 restaurant openings over his career and co-created brands like Tin Star, Pei Wei Asian Diner, Velvet Taco, and Banh Shop.

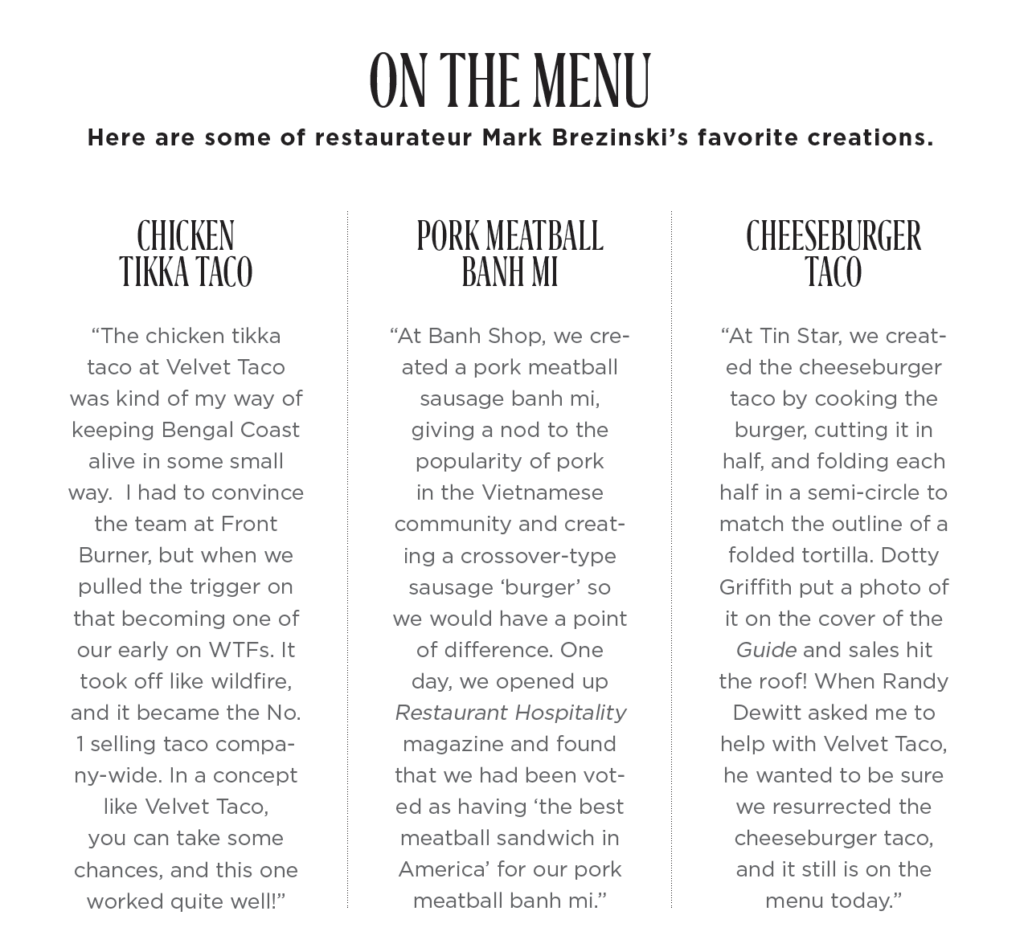

“I’m a very private person,” he tells me as we settle into lunch to talk about his latest adventure, scaling Tokyo’s popular Marugame Udon with longtime friend Pete Botonis. A restaurateur who “expects people to know what he thinks without expressing it,” Brezinski has a profound understanding of food and the culture around eating. He wastes no time going into a detailed lesson about curry after I confess that while in college, I ate curry udon every day until I smelled like it. He told me the word curry itself means sauce—much like my nana and many Italians use the word gravy—that the curry leaf has somewhat of a nutty flavor and isn’t often in curry dishes, and the Japanese curry served at Marugame has a light, almost sweet heat that was influenced by Spaniards in the spice trade. Brezinski, who has traveled the world on culinary adventures with five-star chefs and used his palate to create dishes like the spicy tikka chicken (one of the most popular items on Velvet Taco’s menu), says he doesn’t consider himself to be an expert—and he’s definitely not a chef. His idea of making it in restaurants is to be seen as a successful businessman, much like his parents, who ran a pharmacy, or his Polish grandfather, who opened a butcher shop in New Jersey after immigrating to the United States.

An introvert who’d rather spend time with his dogs, Brezinski needed a couple of attempts to realize marriage wasn’t for him. And he’s not the type of guy who will let you order for yourself—especially at one of his restaurants. Questions like “What do you want to drink?” are rhetorical. I was served his favorite, a blend of two iced teas. And when it came time to order, he curated a spread that included the Curry Nikutama udon bowl, shrimp and ribboned vegetable tempura, some seasoned grilled vegetables, and an egg salad sandwich from Marugame Udon’s Katsu Sando (Japanese sandwiches) menu. “You eat every day, but you die only every once in a while,” he tells me. Brezinski is a tad eccentric, but he damn well deserves the title of the “idea guy.”

A lot is riding on the success of Marugame’s U.S. launch and expansion. Its failure would be the final nail in the coffin of Brezinski’s long-running career, and its success would be the perfect comeback after losing it all when his attempt to mainstream Indian food with Bengal Coast left him bankrupt.

It was a miserably cold night in late January 1991 when Brezinski made the drive from Houston to Dallas for a job interview with Rick Federico. At the time, Federico worked with Chili’s Grill & Bar to open a North Texas location of a popular San Antonio Italian restaurant. It was a low point in Brezinski’s life, he writes in an early draft of an autobiography he shared with me. He was 35 years old, freshly divorced from his first wife, and still recovering from surgery to remove a benign brain tumor. With just $120 in his pocket, after selling his first business for “peanuts,” all he had to offer was a master’s degree from the School of Hotel Administration at Cornell University and experience managing Nino’s, a well-liked Italian trattoria, for legendary Houston restaurateur Vincent Mandola.

The interview didn’t begin well—you’ll have to read the book one day for all of the details—but let’s just say he lost track of time while golfing with a buddy and showed up dressed for the links—soft spike shoes and all. But a week later, he was hired to join the management training program to launch the first North Texas location of Phil Romano’s Macaroni Grill.

He went on to help establish a handful of other concepts, and “little by little became known as the guy you went to if you wanted to create a concept,” he says. That worked well for someone who admits he has little patience when it comes to staying in one place too long. “That fuse fizzles out when things become less creative and repetitive,” he says.

“I start to feel like a fish out of water, always thinking, ‘What else can we do to make it fun?’”

It was that kind of thinking that ended his career with Brinker International (which owned Macaroni Grill and Chili’s) after working with Romano for “four months of hell” to roll out EatZi’s, and caused him to walk away from Pei Wei after seven years because he grew bored with a menu and was itching to do something new. “If you’re not happy, don’t infect the people around you with your unhappiness,” Brezinski says, punctuating the thought with eight telling words: “I left with a nice pile of cash.”

He knows what it’s like to fail and fall—hard. After he pumped a lot of his own money

into opening Bengal Coast, Brezinski’s beloved restaurant closed in 2010, after a rough two and a half years. The location in The Centrum, the struggling economy, and the progressive menu were all a bit too much for Dallas at the time. “I lost my ass because I was trying to create the P.F. Chang’s of Indian food,” he explains. “I don’t care who you are—failure hurts.”

The loss hit him hard, and for a man described by friends as the epitome of optimism, he fell into a deep funk. “You couldn’t find me for two years,” he says about the dark time. Brezinski—whose in-the-works autobiography recounts his life from growing up in small-town Little Falls, New Jersey, to this final chapter—says he wants the story to chronicle his failures to help other business leaders realize that missteps are just part of the journey. “I’m still proud of Bengal Coast, despite it going bankrupt,” he says.

His return to restaurants has been as triumphant as his start—and it all began with humbling himself in one of his famous “mini-novel” emails to a few close friends in the industry to see if anyone needed help. Front Burner Restaurants CEO Randy Dewitt answered the call. The two first met years ago, before Dewitt sold his Rockfish Seafood Grill to Brinker International. They reconnected after Brezinski sold Tin Star. “I remember thinking about how innovative and creative he was and just nurtured our relationship over the years,” Dewitt says. “When it came time for me to create Velvet Taco and put together the team, Mark came to mind because it was my first casual—and he is one of the early pioneers.”

But it isn’t just Brezinski’s history in the space that makes him attractive to restaurateurs; it is his understanding of food and flavor. DeWitt explains: “Have you ever watched that Netflix series Chef’s Table when they show these scenes of someone so focused on what they are doing? That is Mark. It is not just food. He is the entire experience. He will walk in and say the music is wrong and you have to agree. People who work with him recognize his level of genius and want to please him.”

YUM! Brands executive Christophe Poirier felt the same way when he reached out to Brezinski to help launch Banh Shop, a fast-casual eatery highlighting Saigon street food, focusing on the Vietnamese banh mi. “Many creative guys, they are working on renovation; they take something that exists, then polish it and make it new. Not Mark,” Poirier says. “His capability is to create a new blue ocean.”

In what he calls his “last hurrah” in the business, Brezinski is once again teaming up with early partner Pete Botonis. The two have known each other for more than 25 years and first met while working at the Southwestern-inspired Canyon Café and later reconnected at Pei Wei. This time around, Brezinski was the one to pick up the phone when recruiting the right partner to help scale Marugame Udon throughout the United States.

Backers of the brand, which has more than 1,000 locations in 13 countries, had reached out to Brezinski to help it gain a foothold in Texas. He now has an agreement to oversee a five-year expansion of the chain in the entire U.S. He and Botonis opened the first area location in late August and plan to open a second by the end of the year on Greenville Avenue. From there, they plan to open eight more in the first half of 2021 and spend the rest of the year growing the franchise side of the business.

They are the yin to each other’s yang. “Mark is the artist of brands when it comes to conceptualizing,” Botonis says. “The people and product are the most important to him—and then policy and procedure. It is not unlikely for him to be at the restaurant on Saturday and Sunday when most executives are at home. He is hands-on.”

Brezinski likens his role at Marugame to that of a tailor. “They brought me a suit that they love. They didn’t want to get rid of it, but it didn’t fit them anymore. The fabric was 100 percent usable, but the style needed a little tweaking, so I let it breathe,” he says. Some of the alterations he has made to the concept include opening up its typically cramped layout and exposing the kitchen. He also added new menu items, like the trendy Katsu Sandos.

Given his passion and genius, many of Brezinski’s peers don’t believe he will walk away from the business at the end of his contract with Marugame. But the restaurateur says ultimately moving on to a place in life where he can share his experience is where his heart is at. “I don’t want to get emotional,” he says when asked about what he wants people to learn from his story. “I want people to have hope—to persevere. Read my story and realize you can have no money and then have money again. You can have no job and have a job again. You can be around people you think are better than you and realize you’re just as good. Learn to be who you are and who you were meant to be—and be OK with that.”

Story by Bianca R. Montes